In the 1930’s, as cars became mainstream and more drivers were on the road than ever before, the first drunk driving laws started to become law. Almost immediately after, law enforcement began seeking ways to identify drunk drivers in a way that would hold up in Court.

Enter Robert Borkenstein and Dr. R.N. Harger, who in 1953 would transform the enforcement of drunk driving laws by inventing the “Drunkometer,” the predecessor to the modern breathalyzer.

So far-reaching is the impact of the breathalyzer that today, every state punishes motorists in some form or another if he or she refuses a breath test. Nearly one million people in America were arrested during 2017 for driving under the influence of alcohol, and some 90 percent of cases involve breath-alcohol forensic evidence.

The technology’s long history is documented in a new book written by several criminal justice and forensic science scholars that explores just how much law enforcers and the courts have come to depend on breathalyzers to punish lawbreakers despite challenges to their reliability.

How did we get here?

Borkenstein served as a criminal photographer in the Indiana State Police before becoming a professor and inventor at Indiana University. His first contribution to the technology of law enforcement went on to become the lie-detector test.

Borkenstein’s pioneering work on the breathalyzer, however, is by far his biggest contribution to law enforcement.

Early iterations of a detection device were known as the “Drunkometer” and “Intoximeter.” But it was the arrival of Borkenstein’s vastly improved “Breathalyzer” in 1954 that vaulted the technology forward and made it seemingly synonymous with drunk driving enforcement.

While the technology is known today by numerous different trade names, “Breathalyzer” as Borkenstein coined it is still the term widely used to refer to any device that seeks to measure blood alcohol concentration in a driver’s breath.

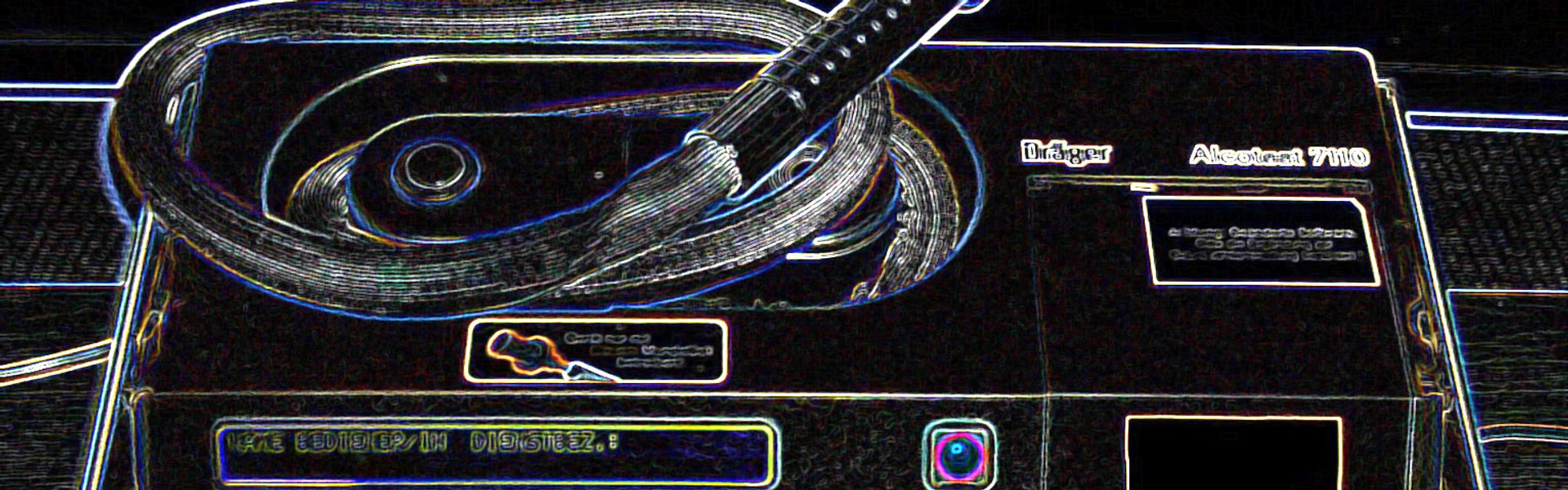

“The technology available for breath-alcohol analysis has improved considerably since the days of the Breathalyzer, and the use of micro-processors allows automated sampling of breath, detection of mouth alcohol, and calibration control of the accuracy of results.”

After working through several prototypes, Borkenstein’s invention was first adopted by police in Canada before exploding in popularity among law enforcers across the United States.

What helped truly propel the breathalyzer to national attention was a landmark study led by Borkenstein at Indiana University that helped establish the now widely used legal threshold of 0.08% blood alcohol concentration for determining intoxication in a driver.

Between the 1950s and the end of the century, over 30,000 different models were manufactured and sold.

“It is difficult, if not impossible, to think of any item of scientific equipment, other than the microscope, that has had such a prolonged and important application in forensic science. The Breathayzer can surely be considered to be to law enforcement what the Douglas DC-3 was to air transport.”

The Breathalyzer Today

In recent years, a debate has raged as to whether breathalyzers truly are accurate enough to be relied upon as heavily as they currently are.

An investigation by the New York Times in 2019 found that breathalyzers could generate inaccurate conclusions at an “alarming” rate, mostly due to lax maintenance by police departments and programming errors by manufacturers.

Judges in just two states – New Jersey and Massachusetts – were forced to throw out over 30,000 breathalyzer tests during a recent 12-month period after determining that they were unreliable. The Times found that some devices had produced blood alcohol concentrations as much as 40 percent too high.

As defense attorney Joseph Bernard put it, “If we are going to put people in jail and punish people, take their liberties away, take their license away, we have an obligation to be accurate”